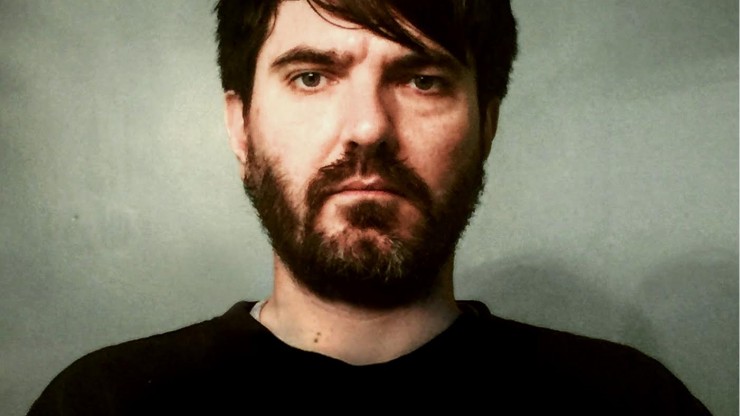

The Salem Film Fest selection committee is already hard at work programming for 2018. As usual, we are looking for films that tell compelling and thought-provoking stories--films that introduce fresh perspectives and ways of looking at and understanding the world. But March is pretty far off still. The good news is, we will be screening a film at the Cabot on November 26th to help satisfy your craving for quality documentary filmmaking. Many of you may remember the excellent film GOOD FORTUNE from SFF2010, directed by Landon Van Soest and produced by Beverly native, Jeremy Levine. This year we have the privilege of screening Levine’s new film, FOR AHKEEM, which he co-directed with Landon Van Soest.

The film tells the story of Daje Shelton, a Black St. Louis teen, as she enters an alternative school to avoid being expelled from public school. Truly an expertly crafted coming of age story, FOR AHKEEM humanizes the complicated intricacies of structural inequality and racism in public schools and in the justice system.

Levine and Van Soest sought to craft a narrative as dramatic and compelling as a fiction film, and rather than take a passive, fly-on-the-wall approach, the filmmakers collaborated extensively with Shelton in crafting the story. The result is an immersive journey into the life of one teenager, who like any teenager, struggles with algebra, hangs out with her friends, has a boyfriend, and occasionally argues with her mother. Beyond those typical teenage experiences is the spectre of death that looms as an ever-present reality. I had the opportunity to chat with Levine about his experience making FOR AHKEEM.

KCS: My biggest question for you is, having seen GOOD FORTUNE, and having watched FOR AKHEEM, your interest in social justice filmmaking is apparent. How did you develop an interest in filmmaking in general and how did your interest in tackling what are some really complicated social issues come to be married with that filmmaking interest?

JL: That’s a good question. I definitely knew at a pretty young age that I wanted to make films. When you’re a teenager and you see a film that kind of breaks out of the mold of what you expect, it ends up kind of being a life-changing event. I had many growing up and immediately felt “this is what I want to do.” I think around high school I also started paying attention to the world for whatever reason and realized how screwed up it was. It was a revelation. I’m not necessarily the hugest Michael Moore fan, but the first time I saw BOWLING FOR COLUMBINE, I thought, “Oh, you can actually do filmmaking and make it about something important.” Yeah, that was a big moment for me--that realization. By the time I was applying to colleges I was pretty committed to that approach to filmmaking. [In looking for subjects], we kind of always start with an issue that interests or infuriates us, or feel it needs more attention than its getting. But then really approach it as much as possible as a character story that plays out like a narrative film, and so we definitely are feeling with this piece we’ve taken that the furthest, and it’s the piece I’m most happy with.

KCS: I was really blown away by the film. You captured some really incredible moments. The one that really stuck out to me is when Daje learns Ahkeem is a boy, and at first she is very excited to be having a son, and you guys captured on film that moment of realization that she’s going to have a child who’s going to have a high risk of dying at a young age.

JL: It’s shocking as an outsider where they want a boy or a girl, and I’m talking mostly about white friends and family. You can be happy or you can be like, “I really wanted a boy,” or “I really wanted a girl,” but the stakes and the implications are just so much more extreme for Daje.

KCS: You mentioned in your director’s statement that there were some consultants that you brought in to help you kind of question assumptions that you had made. You were conscious of being two white male filmmakers making a documentary about a young Black woman. Were there any moments where you did have an assumption challenged and it became a transformative moment for you?

JL: There were so many. We had different editing consultants come in and explode the structure in a way that seemed totally insane to me but ultimately made so much sense, having to remove yourself from exactly what you shot--like, how do we best tell this story? In the director’s statement we wrote about how our producer Iyabo [Boyd]actually set up some incredibly targeted screenings. We had a group of Black activists in St. Louis, some academics in St. Louis. We had one screening that was only Black women, or almost exclusively Black women watch a cut. I think a lot came out there. The fact that Ferguson happened was a really confounding thing in production. Because it felt like something monumental was happening. It clearly was hitting on a lot of these themes that we had set out to explore from the beginning, like criminalizing black youth, the assumptions that are made about people, all of that with these awful, lethal consequences. So we shot a lot of it because we didn’t want to miss it. Hopefully in the end film it’s maybe not so apparent, but it took us some time to really figure out, how does this fit into Daje’s story. I think earlier on we had so much more of it [Ferguson footage] but it was happening separately from Daje, and it just felt like we had this crazy footage of police doing these awful things, people standing up and putting their foot down. But Daje wasn’t out on the front lines. She was pregnant. She was really terrified of going out there. Definitely that screening helped bring forth that we just needed to go back to what we set out to do, which was just to tell Daje’s story and what these huge national issues mean to her on a personal level. Obviously being pregnant with a black boy who she’s going to bring into St. Louis and the world, that really became the heart of how we approached it.

We haven’t talked about this publicly, but I think it’s interesting. We debated a lot about how much we need to own up to our position as outsiders, as white filmmakers. I think in that cut we actually had kept in a very brief scene in the moment when Daje is in front of that Obama poster that’s kind of become the poster image of the film. And a few moments after we cut out in the final film, she says, “I don’t want to do this anymore,” and takes off her microphone. I think it’s my hand, my white hand reaches in and grabs the microphone from her. It’s a really small moment to acknowledge ourselves and position ourselves. In the screening, I think it was pretty unanimous, this was the screening of exclusively black women, they were like “What are you doing? This was such a poignant moment and you’re now making it about yourselves.” It was actually great to hear that because for us it’s not a film about ourselves either. We didn’t want to do that either, so it felt like reinforcement to kind of follow our vision and really just let this play out as Daje’s story.

I did talk some more with Levine about how Daje is doing these days. He was at the airport about to board a plane to St. Louis to see her in person when we spoke. I don’t want to reveal too much before the screening, but he says they still talk a lot and that, “she has a lot going that’s really exciting, but she also has incredible challenges every day.” Fortunately, Levine will be here for the screening to give more details in person.

FOR AHKEEM screens at The Cabot on November 26th at 4:30, followed by and Q&A with Jeremy Levine. Tickets are available online or at The Cabot box office.